Summer Waning

It certainly has been a difficult Summer at Backwater Farmstead.

The foie gras season takes a lot out of us mentally, physically, emotionally. There’s a sudden onset of tremendous activity in the Fall, and the daily obligations continue through the cool months and into Springtime, leaving little time for much more than work, work, work.

As the season winds up, we continue to sell inventory at the Covington Farmers Market and online, but restaurant deliveries cease as fresh duck goes out of stock until the Fall.

We have a reasonable need of rest and recuperation after our harried work to produce Louisiana’s own foie gras - and the only foie gras in the Southeastern U.S. - but that need is never really fulfilled, given the tremendous lack of substantial profitability in small-scale agriculture, so we continue on, tired, through the hot months, finding some way to make ends meet until the next season.

However, things haven’t really worked out for us this Summer in that regard, and we haven’t the capital to kick off another foie gras season with any real force. This has led to some reflection on our part as to whether the production cycle is a sustainable way for us to provide for our family.

Thus far, our discernment has led us to the conclusion that we should scale back and produce a lesser volume of foie gras in conjunction with seeking other work to fill in the gaps.

This isn’t our desire, of course, but there are significant barriers to continuing in our former track, such as market conditions and pricing expectations, as well as national food policy … “politics” being the primary influence that ruins any semblance of a free market in agriculture.

Thus, working hard and producing a desirable product don’t necessarily result in economic stability for local farmers.

That being said, we have no intention of throwing in the towel completely. However, we do intend to respond to this situation in the only way that seems to “make sense” (while being completely unreasonable from a historical perspective): casting the net wider by focussing on online sales to reach a target audience that already appreciates artisanal goods produced with traditional methods.

While we’d prefer to adhere to the ideal (i.e. selling locally that which is raised locally), the sad reality is that there is not a high enough concentration of customers who share that ideal where we reside. Few enough eaters eat from their local farmers, and, while there is plenty of foie gras cooked and served in New-Orleans-metro-area restaurants, most of it is shipped from New York.

If you’re a local regular, have no fear! You’ve made the “short list”, and our products will still be available to you, and we do intend to maintain our presence at the farmers’ market.

If you’re not local, your chances of obtaining such yummies as lobes of foie gras, country pâté, foie gras pâté, duck rillons - among other things - is about to increase.

Thanks, as always, to our loyal customers and friends, and we hope to hear from you soon!

Is the Movement Moving?

When we consider “movements”, such as the “Trad Wife Movement”, the “Local Food Movement”, etc., what exactly are we talking about? Most of the conversations about these topics happen through mediated forums rather than meaningful, real engagement within our communities, and so these movements often seem to be more like entertainment channels than effective, real-world forces.

I recently read a quote from Allan Ehrlick, president of the “Halton Region Federation of Agriculture” that went thusly: “Suddenly everyone wants to buy local food, but you can’t grow it in subdivisions.”

While it seems that, within context, he was referring to the federal onslaught against family-owned farmland and the need to preserve it, it struck me that the presumption that “everyone wants to buy local food” might be more accurately constructed as “everyone wants to talk about buying local food”.

I’ve been running a booth at my local farmers’ market for quite some time now, and I can assure the reader that far from “everyone” buys local. We live in an unprecedented era wherein entire regions cannot support themselves nutritionally because the populations of those regions A. do not farm and B. predominantly buy from other sources than their neighborhood farmers.

Let’s say that, for instance, “everyone” in my town decided to “buy local” this weekend. Every booth would be sold out within minutes, the passage of time only being relevant for the sake of receiving funds and handing over goods. The lines would be so long that the streets would be choked with bodies (which itself indicates the absurdity of the lacking infrastructure for local markets and the limitations placed upon them in regards to public commerce).

Despite the ever-increasing availability of information about local food resiliency, sustainable and “regenerative” agriculture, and the importance of eating consciously, local farmers’ markets do not seem to have benefited all that much. Expansion in “awareness” has not necessarily resulted in expansion of markets.

What hurts the most is when you know that your friends and acquaintances know that they ought to be stocking their larders from the provenance that you and other small-scale farmers work so hard to generate and yet fail to “show up”.

It’s an ongoing struggle.

My perception is that Americans fail, in general, to prioritize the #2 item in the hierarchy of human needs and, when they do prioritize it, they fulfill this need as conveniently as possible and not necessarily with the Common Good in mind, i.e. they’re headed to Whole Foods (or Costco, as the case may be) and looking for “Organic” and “Non-GMO” labeling instead of taking real responsibility.

Which is to say, their choices often push dollars out of local economies - out of the hands of their friends, neighbors, and valuable members of the community - and into large conglomerates domiciled elsewhere, whose CEOs may have other primary interests than the ultimate good of their customers.

It is very much the trend to have some working knowledge of the food system these days and to have the appearance of being a conscious consumer in regards to nourishing one’s family, but perhaps the trend would align more with objective moral principles if the consumer viewed himself or herself as a “participant” in community agriculture rather than a “consumer”. In other words “Who is my neighbor?”

Besides being the virtuous means of feeding one’s family, contributing dollars toward local agriculture means that farmers will be there for you when you need them. (I am reminded sharply of the lines at my booth during the beer-virus days (and the sudden drop-off in farmers’ market patronage when grocery store policies became less restrictive and nerve-wracking).) In other words, the complaints we voice about Walmart, chain stores in general, and large banks can be applied to our own lives much of the time when we make decisions that sap the local economy in favor of convenience, preference, and the general placement of our personal gain over that of our neighbors.

As an illustration, local food is not - as is so often claimed - “too expensive”. It reflects - inadequately, in my opinion from hard experience - the labor and overhead inputs of people who are farming at a reasonable scale (i.e. “the human scale”: a historically normal scale, a domestic scale), which requires real responsibility on the part of the farmer. Over-expansion and outsourcing to reduce costs have the eventual results we are all too familiar with. And who doesn’t want to support the incubation and growth of responsibility in one’s community - responsibility for one’s actions, accountability for consequences, real “participation” in the lives of one’s neighbors (which means real, significant human interaction that is impossible both online and at the box store).

Don’t be afraid of relationships, even complex ones - for example, being both a friend and a customer to your local farmer. This is how the heart expands its capacity for justice, charity, patience, and fortitude. Think of the possibilities for the soul to advance in wisdom when conflicts do arise!

I suppose I’ll close with this: don’t settle for the show. Don’t let yourself off easy, because, in the end, life isn’t easy and its hardships can serve to make us better people, better neighbors. At the end of the day, we’re not the center of the universe. We find ourselves only in relation to how we treat others. “Who is my neighbor?” A question that contains its own answer. Strangely enough, taking on the perceived hardship of sourcing as much as your nutrition as possible from local farmers results in your table becoming a center of both ineffable gastronomic delight and of real, authentic culture.

Avec amour,

Ross

The Spirit of Crusade.

The White Horse of Uffington

Non nobis, Domine.

Non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam.

Brother.

I write to you as you perhaps also sit in the sickly glow of a screen, scanning and scrolling for fulfillment. Who shall give it?

"You who renounce your own wills … (The Rule of the Templars)”

Our generation has begun again to strive upward, to break free of mere “Liberty”, a word Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre described as almost “sacrosanct” to the Revolution.

We strive and strive, unknowing, longing - striving in a world that does not understand the spirit of the Crusades enough to hate it. Indeed - I say again - there is no one who hates the Crusades, because there is no one who understands them: the Crusades which were exemplary of Freedom (the renunciation of the self).

Men always seek a challenge, but what is the challenge, and is the road honorable? Is the pursuit mere Liberty (the lack of obstacles to the fulfillment of one’s desires, whatever they may be) or is the pursuit Freedom, which is the acknowledgement of the Divine Order and submission of one’s will thereto.

''Probate spiritus si ex Deo sunt. That is to say: ‘Test the soul to see if it comes from God’ (The Rule …)”

We live in an epoch of unprecedented uncertainty and confusion resulting from the rejection of the Divine Order by our forefathers’ forefathers. Slow degradation and degeneration of humanity through the ages has widened the rift between the male psyche (and its desire for great feats) and its most beautiful expressions throughout the history of the Glories of Christendom.

Consider the Poor Knights of the Temple.

”For if any brother does not take the vow of chastity he cannot come to eternal rest nor see God … (The Rule …)”

Celibate warrior-monks who forsook worldly pleasures, who only ate meat “three times a week” (The Rule …), and who kept the hours in prayer, the Knights Templar are emblematic of a masculinity that existed on another plane, one to which most of us can only aspire to reach, and few will attain.

Abandoning all finery, they consented to a communal life of fasting and sacrifice, up to and including the ultimate sacrifice of their lives in the defense of fellow Christians, the Church, and pilgrims:

It is the truth that you especially are charged with the duty of giving your souls for your brothers, as did Jesus Christ, and of defending the land from the unbelieving pagans who are the enemies of the son of the Virgin Mary. (The Rule, par. 56)

We often think of these men as being constantly and forever at war - men of violence and wrath, and yet often their days were spent in silence and in recollection:

When the brothers come out of compline they have no permission to speak openly except in an emergency. But let each go to his bed quietly and in silence, and if he needs to speak to his squire, he should say what he has to say softly and quietly. (The Rule …)

Silence and prayer, fasting, abstinence, celibacy, the contemplation of one’s death: such was the life of a Poor Knight of the Temple. And why? Non nobis, Domine. Non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam. Not unto us, O Lord. Not unto us, but unto your name give the glory.

They understood the source from which all existence comes, and they wished to live or die by the Truth: “And you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32). Free?

Yes, brother.

Free.

Freedom? The ability to do one’s duty to God, to one’s family, to the Church, to one’s neighbors. In the time of the Crusades - despite the propaganda of the Revolution (i.e. the Revolution against God and therefore against man) preaching otherwise - duty required the willingness to suffer and to die in the defense of all that is Good, True, and Beautiful.

We no longer live under the auspices of the Glories of Christendom. We do not build Mont Saint-Michel, nor Notre Dame de Paris.

The Age of Faith stands as a great and unassailable watchtower - representing the heights to which man can climb when he worships God in all justice - and looking down upon the wasteland of the pride of the Modern Age and its legacies of unprecedented genocides, misanthropic architecture, iconoclasm, and rebellion against the very laws of nature themselves.

The consequences of the ever-shifting seas of liberalism (which is simply another name for subjectivism, rationalism, and relativism - and liberalism is the ideology of both Left and Right!) have finally come hope to roost. There is nothing we hold sacred. Innocence itself will not be spared by the demons of the Revolution as they screech in the streets “We are coming for your children!”

It is fashionable to consider - instead of our own age of infanticide and biological warfare - the Crusades to be a series of genocides and the soldiers who fought in them - many of whom were men of real, heroic virtue - savages duped and cajoled by men of power into a war of empire.

My, how we have been duped and duped again - duped in preparation for more duping yet to come, dunces of the New World Order.

But perhaps our false ideas of “Progress” and the exceptionalism of the Post-Post-Modern Age are finally failing to convince. The propaganda, too often repeated by untrustworthy voices, no longer persuades because it failed to deliver its bill of goods that was only ever - and always will be - a catalogue of lies and deceit.

Brother.

Voices from another age call to you.

I call to you, and I ask of you: will you renounce the old man, “who is corrupted according to the desire of error”, and become the new (Ephesians 4:22)?

Your neighbors - they too are corrupted. To love them, often you must simply oppose them. They may will not to see the light. They may will to live in darkness, in “the desire of error”, the desire of Liberty and the hatred of Freedom. Too love them, again, you must oppose them and bear their hatred, betrayal, and rejection.

The immolation of self in our age begets the suffering of living, perhaps, at times, as a ghost: devoid of friendships, a good job, decent family relations, because it is what living in the Truth demands. It is what the spirit of Chivalry and the spirit of the Crusades demands - and in acquiescing to the demands of the Divine Law and through the mortification of the Flesh and its desires, we will find our crowns.

Wherever you are, brother, you are not alone.

The Sacred Heart, wounded with love for you and for all mankind, sets with its steady, orderly beats the rhythm of your life and stays near to you so long as you stay near to Him - for God never drifts away from us, but we from Him.

God is only far when we distance ourselves from Him and His gifts of grace, which come first and foremost through the Sacraments instituted by the Church he founded, the Church that fostered the Age of Faith, that fed the Templars their spiritual meat.

Will we accept what is offered?

Strength, discipline, austerity, obedience - the pillars of a hope that cannot be shaken by any cinder-block edifice of man.

The children of this world live in darkness, “But the men signed of the cross of Christ / Go gaily in the dark” (The Ballad of the White Horse, G.K. Chesterton).

The powers of this world mock, condemn, and persecute the Church of Christ, “But the men that drink the blood of God / Go singing to their shame” (The Ballad …).

Vive Le Christ-Roi.

Avec amour,

Ross

The story so far ...

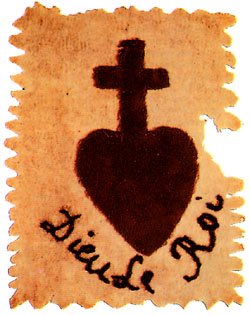

Patch worn by soldiers of the Catholic Counter-Revolution in the Vendée

How did it all begin?

We had posted the following - multi-faceted - cri de coeur on Friday, June 2nd, but things seemed to continue as normal until after the weekend, when, on Tuesday, June 6th, I received the first communication canceling a standing order of chickens. It was followed closely by a second communication from another of our accounts, from which I learned we’d be holding onto some ducks.

The Instagram feed post caption from June 2nd:

Americanization = homogenization = subjugation.

The push to have every mainstream value and holiday represented in some way in our Louisiana ought to make no sense at all to any Louisianais or Louisianaise, unless recognized as a forward offensive by an ever-encroaching enemy that has sought for generations to destroy our unique culture which is so intimately tied to our Catholic identity.

The attempted coup of the month of June is part of that offensive, but I can suggest some antidotes to a false pride:

1. As is our tradition, enthrone the Sacred Heart in your home this month, and place your family under the protection of the furnace of Christ's most merciful love.

2. Wear the Sacred Heart as a badge wherever you go! If you know your history, you'll know that it was meant to be the livery of France (and was that of the Vendéens)!

3. Pray the Rosary for the conversion of souls. Pray it in French.

4. Check out my most recent journal entry on our website.

For God and the King! For God the King! Pour Dieu et Le Roi ! Pour Dieu Le Roi !

After learning that our summer income was in great jeopardy, we experienced, of course, a variety of emotions stemming from the great uncertainty of how to care for our family of seven. I would be lying if I said I did not experience fear, anger, frustration, hopelessness. I reminded myself, with my rational faculty, that God would provide, but that didn’t assuage the tremendous feelings of distress - did I really believe that He would?

I remember some moments of incredulous levity. There is a certain humor to the world crashing down around you in punishment for saying something so salutary, true, positive, encouraging.

We were behind schedule. Chicks were arriving in the morning, and we had the unpleasant and intimidating task of cleaning out one of our buildings that we use as a brooder-house in preparation for baby birds … many of which now had no final destination as packaged products.

It was a mad situation, an absurdity. I was struggling not to explode, and I didn’t really succeed.

I remember sending out an appeal to our PMA members and to our Church community, and many responded, scheduling times to pick up product from the farm or at the Covington Farmers’ Market, but a few families - even several families - cannot consume the volume that is required to keep small-scale farmers in business.

[This seems like a good time for me to encourage you to buy from those who are your neighbors at your local farmers’ market. The greater number of families who decide to simply allow small-scale, local farmers to feed them, the greater resiliency these farmers will have to economic impacts of the sort we are currently experiencing.]

However, a message from a customer and acquaintance - now a good friend - who said he’d be in the area and wanted to stop by to purchase some meat set off a chain of events that can only be explained in reference to Divine Providence.

When Harrison arrived, I began chatting with him as if he had come to support us given the recent difficult news, but he actually had had no idea that any misfortune had befallen us. Once I explained the situation to him, he became very indignant, and it was his Twitter post following this exchange that caught the attention of Evita Duffy-Alfonso at The Federalist. Evita and I had a very good discussion - being Catholic, I knew that she would understand my sentiments in a way that perhaps another journalist could not, particularly the idea that beauty and goodness can result from suffering of this sort, and that God always provides (“Deus Providebit”).

The situation then developed into a sort of conspiracy between Divine Providence and Catholics who were waiting in the wings to follow His promptings. Rachel Campos-Duffy (another fellow Catholic) invited me to be on Fox and Friends for an interview to occur on Saturday, June 10th. Following this interview and the accompanying Fox News headline, our lives changed rapidly and dramatically.

A fellow Franciscan tertiary showed up at the farm to deliver the Denarius.

Harrison had set up a donation site, and the generosity we witnessed was overwhelming.

Catholic media picked up the story, and I spoke with a variety of news organizations, including LifeSite, EWTN, The Remnant, CNA, OSV, and others.

There’s so much more I could tell about the activity of Divine Providence (such as the completely crazy story about our car troubles and how we ended up leaving on a previously-planned trip in an old, beat-up 2004 Odyssey and returning in something far better, and far safer), but I must leave some things to your imaginations.

I am not certain we are capable of properly expressing our gratitude to Mr. Juan - who helped us with the car - and to all those who donated to help our family in our time of need, but I also know, from the words of one, that these good people want “nothing” from us, that they gave to God in giving to us, that these truly were “alms” which we must humbly accept. And yet I have been so inspired and revivified by the goodness of my fellow man that I need to say “thank you”, because I saw so little hope for a Restoration before all of this.

But there is hope.

There is hope, most assuredly, in the Reign of Christ the King, but there may also be hope that the culture wars in our country are not lost.

Case in point: I was persecuted for promoting the Sacred Heart of Jesus and for condemning this “false pride” that celebrates crimes against human sexuality as God created it. How did God respond? He promoted His Sacred Heart all the more, and he cared for my family with unimaginable generosity.

So what next?

I have just finished an interview with Stew Peters today, Tuesday.

And I am not finished. We are not finished. In the face of a Great Reset, it is our duty to fight for a Great Restoration of Christian society under Christ the King, the Creator of human society and thus its proper Head.

Will you fight alongside me?

Our causes:

To support the promotion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Social Reign of Christ the King: Click Here

To purchase a chicken from Backwater Farmstead to be donated to the local Food Bank: Click Here

Chanson pour la Louisiane (Song for Louisiana)

Photo: Family Procession around the farm for the April 25th Major Rogation Day

Bienvenue en Louisiane

Bienvenue en Louisiane

Mais en Louisiane

Les gens ont oublié

La Foi et La Culture

La Louisiane saigne et pleure

Vous êtes venu en Louisiane

Et donc il faut m'écoutez

Bienvenue en Louisiane

Bienvenue en Louisiane

Bienvenue au pays où l'argent

Parle plus fort que l'intégrité

Son peuple est trop faible

Tout ce qu'il veut c'est de jouer

Bienvenue en Louisiane

Où les profiteurs viennent piller

Maman

Vous ne m'avez jamais appris

La langue de mon coeur

J'ai longtemps cherché

Ma vrai identité

Maman

Où sont les ancêtres

Qui pouvent m'apprendre

Les chansons et l'histoire

Ce corps a besoin d'une âme

This Tremendous Weight

A family picture at the grave of my 3x-great-grandfather, Jean Dominique Marie Emeric de Nux.

I considered entitling this short reflection “Love Letter to a Lost Homeland”, but I debate the accuracy of describing the region of my ancestors and of my childhood and adult years as entirely “lost” to Americanization. There certainly is a looming possibility of total loss of our culture, our history, our music, and, most importantly, the practice of our Religion in south Louisiana, but that there is no need for me to specify that “Religion” (but merely to capitalize the first letter of the word) is perhaps a sign of hope.

“This Tremendous Weight” came forth from the depths of my recollection through the various bullet points in my memory as more apt given the existence of a precipice, the proximity of an abyss into which we have not fallen - yet.

First, let us address the glaring problem of the language in which I write to you (yes, to you, my dear fellow Louisianais). Despite most certainly being a sign of homogenization - and therefore lack of independence - and a loose thread in the seams of the fraternal relationships that make us who we are and made us who we were, let’s not fret the use we can make of the enemy’s own weapon. American English, here, can serve the purpose of the multitudinous languages in which the Holy Apostles preached at Pentecost.

The journey we have to take together will lead us back, as did that same evangelization when the Holy Spirit descended in flame, into a more ancient tongue that is indeed also inseparable from the Church, spoken as it was by her eldest daughter and her eldest sons.

My premier ancêtre to immigrate to Avoyelles Parish, Emeric de Nux (Jean Dominique Emeric Marie de Nux), wrote a somber ode to Tradition with the title “Rome ou Malte”. Published in Paris in 1866 by Charles Douniol, it describes the destruction of history, culture, justice, and Religion caused by the thoughtless brutality of the forces of revolution, and, in so doing, perhaps provides insight regarding his reasons for leaving France. Did he still recognize his homeland as one of the greatest incubators of civilization in all of Europe, or was he haunted by the same forces that pursue the supplantment of our own way of life today, here in the New-Old World that is (was?) New France?

The personal history of the de Nux family? We maintain records of our family from the 1500s onward, and we had an intimate brush with the Revolution of 1789 when armed thugs forced the family from its ancestral home near Pau and the new government’s gestapo-like police hunted for Dominique de Nux, compelling him to live in hiding.

The well-known seizures by the revolutionary government of the property of nobles and the Church is perhaps more thoroughly documented than the effects of these seizures on the people of France. One notable (and notably under-noted) example of the rapaciousness of the revolutionary powers in France was the genocide of Catholics that occurred in the Vendée by order of Robespierre after the final defeat of the counterrevolutionary forces of the Armée Catholique et Royale: nuns and priests bound together and cast into rivers to drown (i.e. the infamous “Republican weddings”), infants speared on bayonets, girls raped and hung from trees.

Immigration from France to Acadie occurred prior to these events in France, but, significantly, there are shared surnames between the Cajun families and those in the Vendée. Owls hoot on both sides of the Atlantic: “a l’ombre de nos halliers”, as goes the old march of the Vendéens, “Le Chant de Fidélité”.

Often overlooked is the reality that the invasion and subjugation of Acadie by Britain was not merely political, but religious. Could Acadians swear loyalty to a Protestant king? Did Britain have any great love for Catholics?

To preserve their patrimony, the Cajuns wandered through the wilderness of North America like the Israelites through the wilderness of Sin.

What will we do to preserve our patrimony as we sit aimless in the wilderness of post-industrial modernity?

From the song “Dégénérations” by Mes Aïeux:

Ton arrière-arrière-grand-père a vécu la grosse misère

Ton arrière-grand-père, il ramassait les cennes noères

Et pis ton grand-père, miracle, y est devenu millionnaire

Ton père en a hérité, il l'a toute mis dans ses REER

Firstly, we must address the generational failure-to-transmit. We can blame the illegitimate sale of the Louisiana territory by an illegitimate, tyrannical usurper. We can blame the edict of 1926 banning French in the schools. We can talk of modernization and commerce. We can blame this and that, de choses et d’autres. However, the primary responsibility for the transmission of culture to our children lies with us, their parents.

With what tenacity did the Vendéens hold onto Religion and their fiery love and fidelity to their king? With what all-enduring perseverance did the Acadians carry their way of life upon their backs all the way down to the rivers and bayous?

Are we willing to carry any burden at all? It is easy to say “I’m from Louisiana”, “I’m Cajun”, “I’m Creole”, but only a little less easy to say “Je viens de Louisiane”, “Je suis Cadien”, “Je suis Créole”.

It is easy to say “I’m Catholic”, but only a little less easy to faithfully attend La Sainte Messe le dimanche and on Holy Days of Obligation, make a good Confession at least once a year, receive Holy Communion during Easter, observe the prescribed days of fasting and abstinence, contribute to the support of the pastors of the Church, and “Not to marry persons who are not Catholics, or who are related to us within the third degree of kindred, nor privately without witness, nor to solemnize marriage at forbidden times”.

Do we not know our history? Do we not understand what relief and grace the refugees from Acadie must have experienced, when, at the end of their journey, they were received with the indescribable blessing of a priest, Father Jean Louis Civrey, sent to them by the acting French governor, Jean Jacques Blaise d'Abbadie? Do we underestimate the significance of the first great act of permanent settlement in St. Martinville by the Acadians - the building of the historic St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church?

A people of the Faith. A people of fidelity: “Fidèles à la vrai flamme, Fidèles à leurs enfants”.

I have witnessed all my life the incredible capacity of our people - including myself - in this age to take all of this for granted. We send our children to Catholic schools that are no longer Catholic. We don’t teach the Faith at home, but merely go to Mass on Sundays and expect catechesis to occur via osmosis - or we go only on Christmas and Easter in an attempt to give veracity to “I’m Catholic” (not a Catholic thing to do) … and many go not at all.

We boil crawfish once or twice a year. Sometimes we insult our ancestors by partying with feasts of fresh seafood on Fridays - even in Lent. We take pride in producing a decent gumbo or Jambalaya or dirty rice. These are paltry things to cling to, tattered finery, the mere trappings of a once-great tradition - and even then, bastardized and conformed to the spirit of the age: pleasure, convenience, ease, ceaseless partying … poor memorials for a culture built with self-denial, difficulty, hardship, penance.

It’s a simple and hard truth: If we lose our Faith (as we are now quite effectively doing), we will lose our ability to identify with the ancestors whose very Faith brought them here and whose very Faith inspired them to have many children, and so here you are. Here we are.

“Dégénérations” again:

Ton arrière-arrière-grand-mère, elle a eu quatorze enfants

Ton arrière-grand-mère en a eu quasiment autant

Et pis ta grand-mère en a eu trois, c'tait suffisant

Pis ta mère en voulait pas, toé t'étais un accident

If we do not know that Christ is both God and King, then we do not know what it means to be Francophone. “Vive Dieu, Vive Le Roi !” the Poitevins cried as they were slaughtered by the Bleus.

It is no wonder, then, that we are intent on losing our language in favor of “la langue de les conquis”, as Jourdan Thibodeaux sings avec beaucoup de force in his cri-de-coeur, “La Prière”. And what is the language of the conquered? Not just American English, but Americanism (the current face of revolution): life through a smartphone, life at the supermarket, life through online shopping, life through a car note, life through a mortgage, life through careerism, life through moving every 5 years for un travail stupide and therefore life without close family ties, life through money, life through consumption, life through mainstream music, life through hedonism, life without God, life unlived!

What is the cost? What is the weight?

What is your promise to me and to my children?

And what is my promise to you and to your children, mes chers Louisianais?

Je me souviendrai d'eux, mes ancêtres, et en particulier, et premièrement, de la Foi qu'ils m'ont donnée, and I will give the Faith to my children.

I will also continue to do, as I have done, my part for the culture. I will continue to teach my children la langue des vainqueurs. I will continue to give to Louisiana as it was given to me by the French, du foie gras. De temps en temps, a derivative culture can use an infusion from her motherland, et donc voilà.

You question me. You say, “but Catholicism has become bland and worldly and the priest talks about football from the pulpit”.

This is because you are not attending Mass as our ancestors did. You go to an English-language Mass - written by the self-same, wrecking-ball revolutionary spirit that we fought in 1789 - that will eventually be abrogated due to its all-too-striking similarities with Cranmer’s “Mass”. Worship God with all dignity and reverence as our ancestors worshiped Him: assist at the Traditional Latin Mass that has existed from time immemorial and which unites all the world in universal worship of the One, True God as He Himself has ordained. Attend but once and watch (do not attempt to understand) and allow yourself to be transported into the shoes of Claude de La Colombière or Marguerite-Marie Alacoque as she prayed for Louis XIV or St. Teresa of Ávila or St. Louis IX, King of France, before he left on Crusade … and see if you do not see your ancestors there beside you.

Will you be there, also, the ancestor beside your descendent, praying and asking God for the strength to bear this tremendous weight upon his shoulders?

More poignantly even: imagine you are Beausoleil Broussard overcome during that first mass at St. Martin of Tours in St. Martinville.

A word that the World hates: Crusade.

But we are on Crusade: “Défendons la tradition”. And on this Crusade we have a weapon: the language that bears our Faith and that bears our Culture. It has never been a better time to rehabilitate that fading, but most essential, part of our common patrimony. As Charles de Gaulle said, “How can you govern a country where there exist 258 varieties of cheese ?” I say, “How can you govern a country with thousands of varieties of jambalaya: your mother’s and everyone else’s?” Or rather: “Comment gouverner un pays où il existe mille variétés de jambalaya : celui de sa mère et celui des mères des autres ?”

I look forward to the day when you and I ensemble, mon louisianais bien-aimé, pouvons dire, dans la langue de notre pays, “Vive Dieu, Vive Le Roi, Vive La Culture, Vive La Religion, Vive La Louisiane !”

Lâche pas la patate (mais donnez-la à vos enfants !),

Ross

Our Lady of Prompt Succor, Hasten to Help Us!

Reflection on Beauty

I idealized this life.

It wasn’t a false beauty that I loved - this, I think, is of paramount importance to keep in mind. In fact, the ideal, is, in many ways, reality in potency. It’s not unobtainable per se (although we are not capable of reaching it without sanctifying grace).

It was a real beauty that I loved, an original beauty - one can say with great accuracy - reflecting the original vocation: “And the Lord God took man, and put him into the paradise of pleasure, to dress it, and to keep it” (Gen. 2.15).

Etched into my being now is the oft-quoted, impassioned declaration of the great Fyodor Dostoevsky, “Beauty will save the world”.

It is a profound truth! - and therefore beautiful. But beware: it is true also that salvation occurs precisely because of the sacrifice of beauty. The perfect Man who is God stretched Himself out upon the tree and watered it with His blood, a farmer from His first human breath to His last on the Cross.

In meditating upon the Mystery of the Nativity, is it possible for someone such as me not to weep as I stand amidst the mess of animals and He stares at me from the indescribable nearness of a manger? I tell you that it is possible - because I am hardhearted, and yet I want to weep.

For a farmer, “He is the New Adam” is not merely an abstract theological truth. It is a truth of tremendous and unshakeable and unfathomable nearness, and one that is so necessary as the Beauty of the idealized beloved becomes the Beauty that is the life of sacrifice.

It seems to me that I cannot explain why I must go on farming despite its devastating impracticality. In the perspective of the capitalist, one might even consider it a logical impossibility, an affront against rationality, to attempt to recall the old life of the family farm into the post-industrial, over-technologized wasteland of consumerism in which we find ourselves. (I suppose that this itself stands as the explanation.)

Je dois le faire. It is super-rational.

I have never witnessed so much loss in return for so much labor.

I have never felt such ingratitude from those whom I serve.

I have never had so little (and so much).

Yet -

It is my gift and it is my penance to do this thing that is the very thing humanity needs in order to acknowledge our insufficiencies: Sowing and not reaping and then reaping in great abundance, killing, culling, weeding, burning, losing, gaining, tending, caring … dressing, keeping, losing, failing, persevering in hope only by grace.

I am not here primarily to produce good foie gras (though I fully intend to). I am here to save my soul …

That first glimpse of Beauty - it is still here … here beneath my fingernails, in cuts and scrapes and a gash on the forehead, in a separated shoulder, in the ache of my knees and the wind in my face, in the flowers blooming in spite of (because of? along with?) my sweat-and-blood-drenched t-shirt.

It is here, but I did not always understand its pain. Beauty was the eternal principle. When I said “I shall farm” I saw Beauty only partially, as if through a mist. “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known” (1 Cor. 13.12).

But I must be the sacrifice - an ever-dwindling of “I” in fact, if I will know Beauty fully, “even as I am fully known”.

Ecce Homo, Titian (1490 - 1576)

Veal Boudin and The War.

As I bite into this savory symphony of veal, pork back-fat, rice cooked in veal stock, herbs, milk, eggs, and wine - all stuffed in a hog casing - I am once again confirmed in the knowledge that God loves man.

Not in the superficial way of a lover who lavishes gifts on the beloved - because this gift was born of struggle and suffering and memory and story.

He asked me “to dress it, and to keep it” (Gen. 2.15) - that is, this land - but of course not by necessity.

It is perhaps a crowning moment of our journey back to tradition - both in the Faith and with the land. It’s a sort of birth in the midst of sorrow, like a cheerless Christmas that yet somehow still shines the light of Joy upon the comfortless.

The pigs were born on the last day of December 2021, harvested and butchered this Fall. The calf was the first calf born on our farm (in June 2022) of our family milk-cow, Patty, whom we purchased from some very good friends of ours. It is Patty’s milk that made it into this veal boudin blanc that I have just consumed, along with our duck eggs and our fresh herbs. The dried sage was provided by our live-in intern family.

It is beautiful. It is a symphony.

The sorrow? Perhaps our hardest year on the farm due to the uncontrollable loss of upwards of 300 ducks (due to feed contamination, we suspect), which follows upon the heels of our greatest, most productive, and most profitable year (in monetary terms, anyway).

And so perhaps the sorrow is not.

Because, after all, the vision of our lives that we knew ought to be … well, it happened (is happening).

I did not often sit last year as I sit now and reflect upon God’s love and mercy (and his justice upon my pride). I reflect also upon the pricelessness of it all. There is no price for which I feel I could sell this boudin blanc, because the cost is so high it is irrelevant to anyone but me - I have born the cost intimately, and so only I can understand in any full sense the beauty and the love in its existence. I have killed for it. I have died for it. I have labored ceaselessly for it.

Is it any less than a painting or a stained glass window in significance and pathos?

I have realized on some level through all of this that our farm is idealist in everything that it does, and it does succeed in this, to a degree. However, the obstacles to our success are high. I cannot with any effort convey the importance of our work to a market that is inextricably dependent upon mass production unless I put the very splinters of the plow-handle into your hands.

Many people from across the country have reached out to me in the past months asking about the production of foie gras and for guidance, which is to say “we are not there yet”. When I look at the farms that have made a name for themselves in natural farming or “regenerative agriculture” (spare me, please), I note that the farming itself is not always central (because it is not and will never be compatible with the food industry’s methods).

We cannot yet compete.

My foie gras is not just worth twice as much as the commodity version. It is worth 4x that value at the least (if I must deal in such terms).

There are some chefs and private consumers who willingly pay 2x the price for a superior, local product, but I’ve yet to meet someone willing to pay quadruple, and yet that is the price of context, of authenticity.

That is the - no, there is no price for my veal boudin blanc, and so, in a sense, there is no price for my foie gras: when the community is lost, when the ties are lost, when the story is lost - you will not understand, and I cannot force you to understand.

I cannot fight the battle of dollars and cents when it comes to generating a “product” for sale when I’m pitched against mechanization and tech and wage-workers and massive economies of scale.

But I can fight the long battle of tradition: of educating those who consent to be educated and those who consent to the suffering incurred by the splinters of the plow in order to learn again what the beauty of that participation in “the ongoing act of Divine Creation” really is.

If we are what we eat, after all, then we must learn how to stop consuming commodities so as to cease being commodities to be bought and sold.

So much to announce that BFG will be formulating a structured course to be offered on selected dates throughout the foie gras season. We hope you can join us in the battle to regain the lost traditions of our fathers that made sovereign households … and that made us human.

Pour Dieu et Le Roi,

Ross

Origin Story: Tradition

What is Tradition? A passing-on, a handing-down, a gift from our mothers and fathers, our patrimony, the way in which all of our ancestors are embodied by us, our inheritance, that thing that makes “a people” more than just merely “a population”.

Many of the best culinary traditions are born of something called “thrift”, something that is itself quite literally born in that it originates within the kitchen economy of the family. The greater the family, the more necessary the employment of “thrift”, thrift in the form of bacon, prosciutto, guanciale, salumi, bresaola, ham, capocollo, saucisson, fenalår, various cheeses, rillettes, confit, and - yes - even foie gras.

And yet, in our age of impoverishment of the imagination due to the convenience and commodification of all things, it is precisely these traditional foods that are considered to be the finest and most desirable things - foods that were, when properly contextualized, the work of thrift, the work of the peasant farming economy, the work of precisely those people whom Hollywood has painted as clueless bumpkins in frumpy brown clothing with dirt smudged on their faces.

The foods we idealize, that we place on a pedestal or consider with awe and wonder come from many generations of great vintners and cheesemakers and charcutiers of France, mozzarella masters of Italy, pig-farmers of Spain. “Generations”: family and the great responsibility of forming and caring for and feeding children good things, of handing down the traditions that are the agents of humanization, the very things that allow us to live a cultured life above the level of mere survival, the very things that keep us from being forced to constantly reinvent the wheel.

Ironically, the young couple with no plans for children that galavants around the world sampling the glories of Tradition - views of the Hagia Sophia, sips of the best Burgundy - are consumers of something they’ve rejected.

Ironically, the hobbyist who makes salumi in California with pork from Carolina has abandoned the very nature of the thing he is concocting. Is it “salumi” anyway?

Traditions have become fragmented and compartmentalized, fetishized rather than authentically experienced in their context of seasonality and the liturgical year, experienced in the very liturgy of existence: of marriage, self-sacrifice, births, deaths, sufferings, daily encounters with “the joys and sorrows of this passing life”. What is more liturgical - barring the Mass, of course - than the slaughter of the first lamb born on one’s own farm, the connection to which is one of both affection and necessity?

It is only by dying, by leaving behind the force of our will and pride in the importance of our own lives and wants and aspirations that we can be open to receiving the wisdom of Tradition. Only then can we realize that true achievement is in the passing-on, the handing-down of something done with real love for others, for our families and communities, something done with care and attention to the massive body of knowledge and intuition carried through history by our fathers and our mothers and, if we do our duty, carried by us forward and paid to our children as what is their due.

Ironic again is that truth that we must die to the desire to be sui generis, unique, original - that we must submit to Tradition and receive from it the wisdom of a thousand years - to leave some good mark upon the world for our progeny and not some bitter memory of selfishness and narcissism.

I guarantee that, once the artificial and short-lived, constantly transmogrified industrial “food” system of our nation starts to crumble, only the traditions that have been faithfully fostered from generation to generation will survive, because they are uniquely rooted in place, so deeply rooted in thrift, so deeply rooted in the kitchen economies of the families who live in a locale, and therefore so deeply rooted in marriage and in faith, in joys and in sufferings, and, as we remember most especially this Sunday, in Motherhood.

Food Cost and Consumer Expectations

The average American’s perception of what food should cost is governed by a system in which the real cost of food is invisible to the casual observer. We live in an era of “notional food” that is created based on which vegetable or meat production enterprises are most subsidized by taxpayer dollars. The result is a more expensive food system (tax-wise and health-wise) that yet gives the appearance of cheapness and abundance.

Enter the local farmer who desires to produce a quality product for his community.

Enter consumer skepticism.

Imagine walking into a supermarket and wanting several questions answered regarding each individual product you are interested in buying. Imagine believing that any passing supermarket employee has any knowledge at all about the origins or production processes involved with a given box of goods off the shelf.

No, we know to keep our standards low at the supermarket, and yet we spend hundreds of dollars there each week, when we could be spending the same at the local farmers’ market and acquiring vastly superior nutrition.

I’ll never quite understand how consumer standards leap into the stars at the farmers’ market. All of a sudden, I feel as if I’m a witness on the stand or a suspect being questioned. I might answer questions for 5 minutes straight from a single shopper, receiving a quick “thank you” at the end of a line of questioning instead of a request to buy something.

While I fully support transparency in agriculture and knowing one’s farmer, I also believe that the same criteria should be applied to all food purchasing decisions, and we can’t expect the moon from our local farmers while giving the box store a pass.

After all, if you’re a stickler for healthy food, what’s the alternative to your local farmer? Going back to the supermarket to buy an item from a faceless corporation with no chain of custody you can trace and no certification you can verify? (Who certifies the certifiers?)

Here’s my challenge to all of those who eat:

Go to the farmers’ market for your weekly groceries.

By all means, question the farmers about their production practices.

After questioning them, buy something. Be willing to spend more than you would at the supermarket, because the freshness and quality around you far surpasses that of the supermarket. In fact, say “thank you” and buy a lot.

Let the seasonal produce and meats available determine your meal plan rather than showing up with a list.

Rinse and repeat.

At the end of the day, if we want access to local, responsibly grown food, we have to buy it frequently and eat it with gusto. It’s the foundation of a healthy body and a healthy local economy. Happy shopping!

Avec amour,

Ross

Our Statement on The NYC Foie Gras Sanctions

I don’t eat quinoa.

It’s never been kind to me. It may be lauded as delicious and nutritious, but those little wispy-tailed spheres have only ever given me grief: bloating, indigestion, gas, you name it.

I don’t know much about quinoa.

What I do know is that it’s a grain (yippee!), it’s served relatively unprocessed, and it kind of looks like couscous (which doesn’t give me violent diarrhea, and is a fun and enjoyable iteration of pasta).

What I also know is that quinoa consumption in the U.S. is a startling case of animal cruelty. In this case, the animals involved are human, so I can speak more intelligently about the issues at stake because I am also human, and have a certain understanding of the human intellect, human anatomy and biology, and the needs of humans in general.

To make a long story short, because of the high consumption of quinoa by 1st-worlder Vegans as a “cruelty-free meat substitute”, poor Peruvians and Bolivians can no longer afford their heretofore staple grain. According to an informative article published in The Guardian, “Imported junk food is cheaper. In Lima, quinoa now costs more than chicken.” In short, “It's beginning to look like a cautionary tale of how a focus on exporting premium foods can damage the producer country's food security.”

Joanna Blythman even throws in a helpful “Embarrassingly, for those who portray it as a progressive alternative to planet-destroying meat, soya [sic] production is now one of the two main causes of deforestation in South America”. See the full article here.

I don’t know much about quinoa. It seems like there are some areas of concern regarding its production, but I don’t know that I can speak definitively on whether it should be banned without manifesting my extreme bias.

But let us turn our attention to foie gras, which is made with the help and assistance of ducks right here in the USA.

In particular, let’s focus on foie gras farming in upstate New York. Now, I am no fowl (although at times I smell that way), but I spend a great deal of time with these birds, and I am fairly well-versed in their anatomy and physiology, their preferred diet, their capacities for dealing with certain foods, mineral deficiencies they are subject to, as well as their likes and dislikes.

For instance, ducks will often voluntarily consume sticks and rocks, spiky crustaceans, fish that seem too big for them to handle (whole), snails, small rodents, a variety of vegetable life, and even things you’d really want to prevent them from eating, such as plastic, metal … you get the picture. They’re like pig-dogs with feathers.

One would be hard-pressed to argue that a smooth plastic tube with a rounded end inserted gently (not “shoved” for profitability’s sake!) down the esophagus — stretchy, keratinous, and sans cartilaginous rings — of a Moulard duck. In fact, the Moulard has been developed quite specifically for foie gras farming, and so it’s uniquely suited to the practice.

Simply put, we’d have to argue that a wild duck has masochistic dietary habits if we wanted to press the matter.

Because, of course — and what the people for the “ethical” treatment of animals that will no longer exist if we acquiesce to their agenda won’t tell you — waterfowl also gorge themselves in the wild. That is, they make foie gras. It’s a migratory ability that all breeds farmed for foie gras also possess. Ducks store fat naturally in the liver (the “foie”). Humans don’t. It’s a major biological difference.

And this brings us to the crux of the matter. Is animal husbandry qua animal husbandry essentially cruel? And to judge animal husbandry with any equity, we must consider it at its best, because if it can be practiced in such a way that animals and the humans that care for them are both respected, then it is not essentially cruel.

But a duck must be respected as a duck. A human must be respected as a human.

One thing that is certain is that all animal husbandry involves biomimicry. The extent to which the animal can perform its natural behaviors and also be healthy and content in terms of its needs determines whether that biomimicry is exploitative or co-productive.

I’m not going to go into the philosophy of farming. Suffice it to say that I pursue farming practices that are co-productive. I am producing something special with the animal in all of its natural abilities and proclivities vs. exploiting the animal for mere profit.

Farming isn’t that profitable anyway. (Trust me. Don’t get into farming for the money.)

What I will say is that the kerfuffle in New York City is not about animal welfare. It’s about political posturing and “animal-rights activists” (is this a tongue-in-cheek phrase?) who truly wish to ban all meat consumption. Just read their mission statements. (Throwback to the quinoa craze: could those suffering farming families possibly be the same families who’ve fled to Sullivan County to farm foie gras? Perhaps at least they share some gripes with those people.) Do 1st-world bleeding hearts care about the real effects of their lobbying on man and beast as long as they can force a strange and very questionable agenda that opposes animal husbandry carte blanche?

Why else would a grand total of zero city-council members accept the invitations to visit the foie gras farms in question, but are completely content to destroy the fragile economy of one of NY’s poorest counties? Why else would these animal-rights activists target the minuscule world of foie gras farming rather than toxic, pollutant-ridden commercial swine batteries or the massive, bird-and-farmer-exploiting commercial chicken industry?

Let’s end where we began.

What do these council members know about foie gras farming? (What do they know about farming - period?)

What are the pre-conceptions that animal-rights activists are bringing with them to the table along with the bowl of cashews (another human rights issue, by the way)?

What do these people know (or care to know) about waterfowl biology?

What do they know about the South American immigrant families who work at these farms?

What do they know about the … wait for it … not French, but Israeli immigrants … who started NY’s largest foie gras farm?

What do they know about the economy of Sullivan County?

On the other hand, what do they know about election cycles, political polls, and which hot-button issues to exploit to press their personal interests or their pet agendas? Pun absolutely intended.

We’ll let you be the judge. Meanwhile, we’ll continue with our mission to carry on the important culture and ancient tradition of foie gras farming, respecting the land, respecting the animals, and respecting the people who have this vocation in life to steward the earth.

May God bless you, and may God bless Louisiana.

Avec amour,

Ross

Pas Végan

Veganism.

Veganism is profoundly nihilist.

It seeks to do the least amount of “harm” by reducing humanity to a ragged tribe of half-starved herbivores who, ironically, must still kill to eat (more on the quiet life of plants here).

Veganism and its offspring, the animal rights movement, manifest themselves in their most neurotic form in stories like this one, where, in short, a woman rambles on about her adopted “daughter”, a Cornish Cross chicken she rescued from a factory farm.

The irony in all of this is that there is no continuation of life without death. The great economy of the earth gives germination and birth through death and decay. The dying trees and fallen leaves and deceased stag all feed the next generation. If we all lived and only lived, food would most certainly be scarce.

Without animal consumption, there would be few animals to live comfortable, ecologically beneficial lives.

”Snow”, the rescue-chicken, would never have been hatched.

Death begets life, and the cycle continues.

So why broach the topic? I’ve had a few conversations - which I enjoy! - with good people genuinely interested in how foie gras is made and whether I use a funnel to - as the animal rights activists say - “force-feed” our ducks.

You see, the optics of Gavage (the practice of using a funnel during the finishing process for foie gras) are extremely important to the Vegan/animal-rights movement. The image of a funnel down a duck’s throat is easy to anthropomorphize as “painful” and “cruel”, and the animal rights movement has successfully convinced people of various political persuasions that the practice of Gavage should be banned.

In that vein, I would suggest they add finishing cattle with grain (or - God forbid - having them eat their own regurgitated forage) to their list of cruel practices that should be ceased forever.

People who fail to think critically often bend like a reed with the wind. If science supports mainstream beliefs, they praise the merits of science. If science contradicts those beliefs, they ignore it.

It would be a very strange idea to suggest to an animal-rights activist that the duck does not think he is suffering when being fed during Gavage, because a duck is not a human being, and does not have cartilaginous rings maintaining a rigid esophageal structure, but rather enjoys a flexible, keratinous hose-like esophagus capable of transporting the strange menagerie of objects a duck will ingest (rocks, crustaceans, and the odd lost toy not being the least bizarre of which).

That does not mean that animal agriculture of the sort we practice (i.e. a rotational, pasture-based, free-roaming system that allows the duck to be a duck to the full extent of duck-ness) is not at times uncomfortable for our flocks of feathered fowl (though far more comfortable than the industrial battery farms). In all forms of animal agriculture, we are asking the beast to do something he wouldn’t necessarily have the precise inclination to do in the wild. We are honing in on some particular aspects of the animals’ biological capacities.

However, the ducks exist and live the best life we can give them precisely because we have designed for them a purpose that required their breeding and hatching. The Backwater duck is a duck and experiences duck-ness because Backwater Foie Gras came to be and continues to be.

And, if you are of the sort that believes life is good, then you will be happy for our beautiful birds.

If you are a nihilist, I cannot help you. If you are a Vegan, I urge you not to dissociate yourself from your slaughter of plant life.

Food and Responsibility

At one of the farmers’ markets we worked last week, I was on the receiving end of a couple of questions and comments that came from a place of irritability, misunderstanding, and perhaps frustration. I’ll briefly recount them here:

“Do you have any pâté today?”

“No, sir. We are sold out. It goes fast, but try us in a couple of weeks!”

“Last time, you didn’t have it. If you don’t have it now, why would you have it then?”

“Is there a real farmers’ market somewhere with actual farmers or is this supposed to be it?”

“Ma’am, this is a real farmers’ market, and everyone here is an actual farmer.”

Certainly, when we shop often at the supermarkets, we tend to bookmark in our minds particular stores that have particular items we want at a particular location within that store, and we expect to be able to find what we’re after 99% of the time.

The supermarket is truly a modern marvel, but, by design, it does not contain fresh goods that are truly local - that is, goods that come from the farms and businesses that exist in the more-or-less immediate vicinity of a supermarket.

Why? Because the supermarket operates with complete dependency on the convenience that it can provide its shoppers, and the more convenience, the more sales.

The supermarket model, by necessity, competes with historically normal food suppliers.

There’s not even one chance in a million that the person who raises cows at a commodity dairy farm is even remotely involved with the various cheese products under various brand names that contain his milk. He’s abdicated responsibility to the end consumer (and transparency along with it).

The convenience of the supermarket - the marvelous, multi-colored aisles full of every kind of edible (if we can indeed use the word) - is dependent upon an extremely expansive catalogue of factories - not local kitchens, not local butcher shops - that do one thing and one thing only, like an infomercial brownie pan. These factories buy a few commodities as cheaply as possible (necessitating a commodity market, of course) and stamp out one ore two items that are somewhat digestible and market the living hell out of them until the stockholders are happy.

And so the commodification of nutrition, at the end of the day, does not serve the needs of the consumer. It’s not even designed with nutrition in mind.

On the other hand, what are some of the motivations for starting a small farm that only serves one or two local communities?

Not extreme wealth (We still know we deserve a BMW. We’re just not expecting it.)

Satisfaction in one’s labor.

Changing the food system from the grassroots.

Care for Creation/nature/the environment.

And certainly not least of all, care for the health and well-being of one’s neighbors.

Food, especially animal protein, is slow by nature (hence the “Slow Food Movement”). Unlike the industrial food system, small artisanal farms aren’t interested in artificially accelerating the production process. We just want to do it well.

We only want to do it if we can do it well.

It takes 4 weeks to make duck prosciutto, but it takes 15 weeks to make a duck that will give us the best duck prosciutto possible.

Enfin, we love our customers and we love that they love our artisanal goods! That love and appreciation is a significant reason for our work. If we don’t have pâté one day, I promise it’s not because we’ve been lazy. Most likely, we had to put on one of our many hats and prioritize a certain task based on the ever-attendant, always-numerous variables of raising ducks from one-day-old to 15-weeks-old to 8-week-dry-aged saucisson sec!

We will never abdicate our responsibility to generate ethical, wholesome food in favor of a quick profit. We’d rather a peeved customer than an unhealthy one!

But ask, and you shall receive! We’re really good about special orders and providing timelines. We’ll see you at the next farmers’ market!

Avec beaucoup d’amour,

Ross

What Local Food ISN'T

LOCUS >

LOCALIS >

LOCAL

A few caveats in reference to this discussion:

There’s a great deal of arbitrariness in reference to what a specific locale is or isn’t. Modern political lines were quite literally drawn on a map to divide territories for the purposes of government. Granted, geography could have come into play at some point, but we all know that cities, towns, districts (especially school districts) have an element of the arbitrary.

More of the arbitrary: What does “local” mean? Its literal definition is “belonging or relating to a particular area or neighborhood, typically exclusively so” (Oxford Languages). But in the practical sense? I don’t really know. I’d like to think that a particular “area” or “neighborhood” forms somewhat naturally around common natural features, common needs, common desires, common goals, common culture. It’s difficult to say exactly what “local” means in terms of “local food”.

My working sense of “local”: For the purposes of this conversation, it seems to me that there is a common notion of the Northshore in Louisiana (Covington, Mandeville, Madisonville, Bush, Folsom - and the surrounding areas) and, correspondingly, the Southshore (Metairie, Kenner, New Orleans, Jefferson, Algiers, etc.). The larger locale that encompasses these areas is considered Southeast Louisiana (the toe of the boot). Let’s keep things simple and deal with two smaller locales fitting within one larger locale.

So! In the world of Southeast Louisiana, what is local? Personally, if I can’t reasonably get to the source of the particular goods that I need and back home within a few hours, I’m not going to think of that producer as local.

Modern transportation allows for a slight expansion of that idea. For instance, I can take a morning drive to New Orleans in under an hour, do what I need to do there, and return home to Bush before noon. 150 years ago, I don’t think I would have considered New Orleans “local” to me.

This has led to a bit of intellectual and cultural laziness.

Instead of researching where I might find high quality mushrooms in my general vicinity of +/- 10 miles, I might just drive to Whole Foods (20-25 miles) just because I know I can get some halfway decent mushrooms there. Is that a morally righteous choice? Probably not, but it’s the easy choice, and sometimes, in our busy lives, easy wins.

I know, I know. I’m preaching somewhat to the choir here, but hear me out. The real danger is when the moral and cultural ideal of “local food” becomes subservient to profit and convenience, even if ever so subtly.

And yes, of course I have an example, because I’ve witnessed this first-hand, second-hand, and third-hand.

Exhibit A: A few local Southshore restaurants advertise dishes featuring “local pork”. Said “local pork” is actually from a fairly large farm 300 miles away in another state. Now, this is nowhere near to being in the same category as the false advertiser who calls CAFO pork “local” merely because it’s produced in the US of A, but it’s a slippery slope. Because, guess what? Local pork actually exists in this case. There are not one, but at least two local pork producers (both actively working to expand their operations) that are located within 100 miles of these restaurants (and which actually exist within the same locale of Southeast Louisiana).

Exhibit B: A few local Northshore restaurants encourage patrons to “eat local” and “support local businesses”, but essentially do not do either of these things, because the food they serve does not come from local farms. It comes off of a SYSCO delivery truck. God bless capitalism, but at least practice what you preach … or have the guts to preach what you practice!

Exhibit C: I’ll even pick on farmers this time around. A local Northshore farm advertises seasonal meats, which they buy in from an out-of-state farm even when another farmer less than 30 miles away in the same locale regularly raises the livestock they plan to offer for their seasonal special. THAT AIN’T LOCAL!

To what can we attribute all of this baffling tomfoolery? I don’t think we can pen it down to one vice or the other. I’m certain we could all name a few vices … But here are some virtues we all need to work on for the benefit of our local food economy (which makes this endeavor other-serving, but ALSO self-serving):

Make An Effort: Before making a large purchase of food for your family or your business, ask around, look around, do some research, visit your local farmers’ markets (all of them), visit your local specialty foods stores. Don’t settle for good marketing.

Practice What You Preach: If we’re going to give “local food” lip service (more of which is currently given than actual patronage), then we need to buy into the local food economy. Coca-Cola is never going to produce a local product, so instead of wasting money on stock that will only later be sold to pay for medical bills from a life of eating COSTCO plastic, invest in locally-produced, nutrient-dense, health-amplifying foods.

Don’t Be A Jerk: If you’re a business-owner, the reality of competition can often seem like constant warfare, but it doesn’t have to be! A little good will and cooperation with your neighboring businesses can go a long way, and actually lead to more diversity in the marketplace (through communication/collaboration) than the traditional notion of constantly trying to find a way to kick your competitors in the teeth.

So what isn’t local food? Local food isn’t “local restaurant” fare, per se, unless the food that the local restaurant serves is also local food. In other words, it ain’t local just because it was purchased locally. If the second half of the dollars from that purchase are sent off to an industrial food aggregate in Iowa, of what value was the first half?!

One final note: It’s not just about money. Money is important, of course. “Money makes the world go ‘round” and all that. But the local food economy is also about the economy of resources and fertility. We have to think about how things are done and whether they are done well or poorly, because human health depends on 1. quality food, 2. produced with sustainable and regenerative methods, 3. that increases the overall health of the local ecology and the human and animal populations as time goes on.

It’s nigh impossible to know exactly the origin and living conditions of that white, antiseptic-looking, triple-sized chicken breast wrapped in plastic at the restaurant supply story, and you might not want to guess.

Get to know your local farmers. Get to know your local farms (ask for a tour)! Eat what local food IS.

Re-Inventing “Local” in a Pandemic

I’m not going to go into detail about what I think COVID-19 really is or isn’t. Suffice it to say that the virus, or the government’s response to the virus, has created unique challenges for all of us. This post is about those who’ve stepped up to the plate.

The day that COVID-19 became big news, we were negotiating the final details of an agreement with a restaurant distributor. That nascent agreement evaporated as restaurants began shutting down or modifying their menus for curbside service.

Many local farms get the majority of their business from restaurants. The significance of this is that when people patronize local farms, it’s often at the restaurants and not during grocery runs. See this NYT article.

We farmers have much to thank our chefs for. The chefs in the New Orleans metropolitan area and the Northshore area believe strongly in using the best produce that is available locally.

What this relationship between local farms and local restaurants means, though, is that orders that were placed months in advance suddenly could not be received, and we small-scale farmers had to (have to even now) scramble to retail massive inventory that was already spoken for until CV hit hard.

The challenge is that the American consumer - myself included - mostly favors convenience over ethics. We’ll sacrifice our ideals at the grocery store or the big box store more often than anywhere else. We’re all to blame for making life difficult on small businesses. I do not exempt myself or my family from responsibility.

Here’s where things get interesting, though. I reached out to the Main family in Folsom and Adam Acquistapace in Covington, explained our situation, and asked if they’d be willing to stock some local meat from local farms. Not only did both grocers place significant orders, but expressed great solidarity with us.

Adam blows me away. His attitude about pulling through these challenges together is what makes the term “local” in regards to our little Covington community so meaningful. Adam assured us he would do everything he could for our business and insisted that we’re all on the same team: grocers, farmers, and restaurants. You may have seen the news about the hot plates he stocks in his stores from local restaurants.

Along with Acquistapace’s (both Covington and Mandeville locations) and Main’s Market, Calandros in Baton Rouge also ordered a fair number of our ducks. We were so busy last week that there were a few days when we worked from dawn until midnight on these orders.

I cannot begin to express my gratitude for the reminder that we are a common human family, and that supporting our local community should always come first.

There are still difficulties ahead, but we are adapting. Duck egg production is in our future, along with offering various cuts from our ducks in addition to the whole bird. You’ll also be seeing us at the Covington Farmers Market in the near future!

If there’s one thing I can ask of you, it’s to buy from your local farmers. … And this asking is really a giving, because the ingenuity, innovation, and integrity of our local farmers is unparalleled. If you want to protect your family from Coronavirus, feed them the best and safest nutrition you can find. Here’s a start:

Fat Duck, Lean Duck

In France, there is a very important distinction between ducks raised with the sole intention of being sold for meat and ducks raised for the production of foie gras. The former are known as “lean ducks”, the latter as “fat ducks” (quite fittingly, if you ask me).

Along with this distinction comes a special set of recipes reserved only for the “fat duck” or the foie gras duck. For instance, magret is specifically the breast of the foie gras duck. You can certainly eat the breast of the lean duck, but if you were dining with a Frenchman, he would certainly correct you if you called it magret (even though magret translates simply as “breast”).

So what is it about magret? We can sear it like a steak (relatively easy … and delicious!). We can make a confit. Or, we can cure it in salt with herbs for a few weeks and enjoy the delicacy known as magret séché. But remember! If we don’t use the breast of the fat duck, then no matter the recipe, it’s not magret, but simply … breast.

Magret is noticeably thicker, juicier, and more tender than the typical duck breast, and carries a good layer of fat beneath the skin. Overall, the foie gras duck or “fat duck” will provide a richer, fattier carcass than the ordinary “lean duck”. After all, the foie gras ducks enjoy a vacation and a hearty diet during their last couple of weeks on the farm.

So why is this important? If you want to enjoy duck, you can go to any number of dining establishments and order a variety of preparations, but the foie gras duck is not so readily available. Blessed indeed is the diner - or, as I like to say, “co-producer” - who lives in the vicinity of a foie gras farm that makes these lovely birds available to the public. I have no bias here.

The key take-away being that, to be sure that you are eating the true crème de la crème, check your menu for the source of the duck, or ask the waiter where they get it, or skip the bureaucracy and order one for yourself. Christmas is coming. The duck is getting fat!

Avec amour,

Ross

*All products available to customers in Louisiana only.

The foie gras duck or “fat duck”.

Seared magret over greens with balsamic glaze.

Into an old life

With all of the insanity and the flurry of activity this Summer, we've had to stop ourselves and take the chance to just walk around these gorgeous acres that we have finally chosen, and that has been everything. For us, farming is a business, but it is more importantly a sacred calling. It's a great sacrifice. It's an extraordinary lifestyle, not unlike that of the Benedictines just south of us.

Stability. Stability is a Benedictine Hallmark. It’s also a blessing. It’s also a curse. We will always be here, the McKnights in Bush, because our work binds us to the land, and our relationship with the land is so much more than a signature on a legal document.

Instead of extended family vacations, going out to eat, or hanging out deep into the wee hours with friends (not that we won't get the odd night off), we will be here, sculpting our art from the earth, determined to make the best foie gras America has ever tasted.